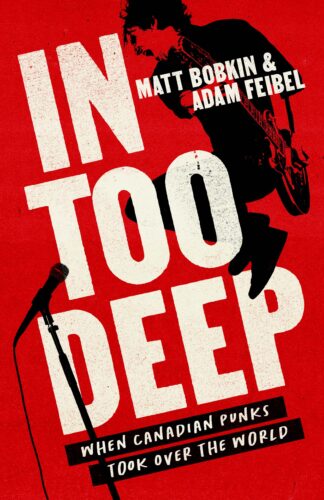

The Alt’s Bookshelf: ‘In Too Deep’ by Matt Bobkin & Adam Feibel

Posted: by The Alt Editing Staff

The Alt’s Bookshelf is a series where our staff highlights some of their favorite books and zines related to music. For the first installment of the series’ second run, Zac reviews In Too Deep: When Canadian Punks Took Over the World, by Canadian music journalists Matt Bobkin and Adam Feibel.

Pop-punk is most commonly associated with sunny southern California; with breakout stars like Green Day, The Offspring, and of course Blink-182. But in their new book In Too Deep: When Canadian Punks Took Over the World, current Exclaim writer Adam Feibel and former Exclaim editor Matt Bobkin contend that that narrative leaves out a crucial contributor to the global pop-punk sound: Canada.

Discussing the book’s genesis with PunkNews, Feibel notes that a band’s “origins [can] get written out of the narrative pretty quickly when you become an ‘overnight success.’ A lot of people in Canada, and outside of Canada, maybe don’t know that Sum 41 is Canadian. When I wrote that anniversary piece about Billy Talent [for Exclaim], that was when my mom found out that Billy Talent was Canadian. They become big enough that they’re just radio bands or MTV bands and those early years of them struggling and playing Legion halls and dive bars to 5 people a night gets overwritten.” In Too Deep, then, is intended as a corrective, a way to remind fans that the story of pop-punk, especially the style that boomed during the early 2000s, is incomplete without mentioning the bands that Canada birthed.

In Too Deep is divided into nine chapters, each focusing on a particular act to break out of Canada between 2000 and roughly 2006, along with a prologue, an epilogue, and a number of asides throughout each chapter that touch on significant bands in Canadian punk history who don’t factor into the particular story the authors want to tell throughout In Too Deep proper. (For those following along at home, these include Propagandhi, Moneen, Cancer Bats, Grade, and No Warning, among others–not bad.)

The book mostly follows a chronology listing the bands in the order in which they “defied the odds to become the world-conquering icons” (6) we now know them to be, as Bobkin and Feibel write at the end of the prologue. The authors detail “a common theme among Canadian recording artists: you could be a big deal in your own country, but in all likelihood, people living outside of those borders wouldn’t even know your name. Neil Young, Joni Mitchell, and Rush were among the rare exceptions. The Tragically Hip was the rule: national headliners, international footnotes” (3). The bands they select for discussion are those who, they argue, were able to break through and become, as they describe Sum 41, “poster boys [and girls] of a pop-cultural moment” (59).

That said, while following a broadly linear path, there’s no central narrative throughout In Too Deep; each chapter stands alone, and a fan of Avril Lavigne’s, say, could read the chapter dedicated to her without feeling lost. While there are a number of recurring figures–among them Island Def Jam president Lyor Cohen, MuchMusic DJ George Sroumboulopoulos, and Blink-182 vocalist/bassist Mark Hoppus–each is discussed primarily in the context in which they appear, so each time Cohen comes up, for example, he is introduced in regards to his significance in that moment.

The lack of a unifying narrative thread could irritate some readers; each chapter plays out like its own short story chronicling the rise of that particular artist, and there’s little explicit connective tissue between them. What unites these nine artists, Bobkin tells PunkNews, aside from all hailing from the same country, is that each of them “challenged the notions of what punk could be and sound like” throughout the 2000s. That, too, could irk readers; purists may be frustrated with the grouping of such disparate artists under the umbrella of pop-punk.

But while In Too Deep might not tell a singular story throughout its exactly 300 pages, that ultimately works to its benefit. It’s an easy book to pick up whenever the mood strikes and put down without feeling like something will be missed in the meantime. Similarly, it’s a quick read, especially for its length, with no chapters longer than 40 pages; additionally, Bobkin and Feibel write in a clear and engaging manner, beginning each chapter with a brief anecdote to set the scene before launching into semi-exhaustive stories of the band’s rises from (generally) humble origins.

These do well to introduce the broad themes explored in each section as well as to give an overview of the bands’ personalities; the very first thing we learn about the members of Sum 41, for example, is that they’re hard-drinking, hard-partying kids who spend every night of tour leaving a trail of “drunken mayhem and physical destruction. They’re barely into their twenties and they’re already on top of the world, shamelessly riding the high of their quick ascent to fame and fortune. They’re young and indestructible” (36). Then, later on, we learn that the band had “planned to film a documentary with War Child Canada about the deadly civil war” in the Democratic Republic of the Congo but ended up “hid[ing] together for hours” in their hotel after they got caught in a gunfight “between the Congolese army and rebel forces outside the Orchid Hotel where they were staying” (64). It demonstrates how far the band had come in a few short years, from rowdy drunk twenty-somethings to would-be humanitarians risking their lives to call attention to wars outside their home country’s borders.

The interviews–with members of the bands, with the reps and managers who helped them throughout their careers, with fans they made along the way–help to keep In Too Deep grounded and, on occasion, add some tension. A particularly memorable example comes when Bobkin and Feibel recount the negative reception to Silverstein’s 2003 debut full-length When Broken Is Easily Fixed. Vocalist Shane Told is forthright about how the criticism got to him: “After that first album came out, I was reading scathing things about our band and myself. I just had to suck it up” (187). For their part, the authors quote from a PunkNews review giving the record the lowest score on the site’s rating system. They point out, too, that this hatred of Silverstein wasn’t limited to just the reviewers themselves: “The comment section largely agreed. Silverstein’s haters were loud, they were mean, and they were tenacious” (187).

Just about every artist discussed in In Too Deep faced significant pushback when they began to make waves, and those moments help create some genuine pathos. One of the authors’ greatest successes is the way they’re able to flip the popular narrative on artists–like Avril Lavigne and Simple Plan–long considered to be corporate products co-opting the aesthetics and language of punk to sell back to dissatisfied suburban teens. The two appear back-to-back early on in the book, and Bobkin and Feibel spend significant portions of both chapters dedicating to establishing the punk bona fides of both.

Lavigne’s personal distaste for pop music and the machinery of the industry is well-documented, and Bobkin and Feibel don’t belabor the point. They tell a story of Lavigne flying out to LA, “burst[ing] into tears” upon getting into the recording studio, and bristling at the way her label, Arista, “keep[s] trying to make me Faith Hill” (79). Once given more control of her sound and her songwriting, they write, she leaned into “edgy hard rock” with “punchy guitar riffs, chunky power chords,” and angsty lyrics in an attempt “to break down the walls” her label had built for her, “firmly plant[ing] her flag on the side of the rockers, the skaters, and the punks, in stark opposition to the jocks, the beauty queens, and the preppy kids” (82). Simple Plan’s punk origins are a bit less known, so the authors spend more time diving deep into them. Nearly a third of their section is dedicated to Reset, the project of vocalist Pierre Bouvier and drummer Charles-Andre Comeau before forming Simple Plan; Reset, as Bobkin and Feibel detail, were “rising stars in Montreal’s punk scene,” pulling from “SoCal-style punk rock” and penning songs about “big-picture issues like labour exploitation, environmental activism, and settler colonialism” (109).

Crucially, though, Bobkin and Feibel don’t read as overly defensive of these artists; instead, their posture comes across as merely outside observers trying to correct the record. Their clear appreciation of the artists they cover only adds to the stories they tell, and their enthusiasm never bleeds into idolatry. They steer, for the most part, away from value judgments. Their focus, more than demanding readers treat Still Not Getting Any like Rubber Soul, is on shining a spotlight on their home country and its neglected punk scene. One of the most impressive feats that In Too Deep accomplishes, in the end, is drawing clear connections between all these disparate bands and scenes. It’s easier, regardless of one’s tastes, to develop an appreciation for Silverstein upon learning that they selected Mark Trombino to produce Arrivals and Departures because of his “old-school credibility,” having “produced records by ’90s bands Mineral [1998’s EndSerenading] and Knapsack [1997’s Day Three of My New Life and 1998’s This Conversation Is Ending Starting Right Now]–two of Silverstein’s major influences” (198). Similarly, it’s fascinating to learn that ex-Grade drummer Charles Moniz was Lavigne’s bassist, and it’s depressing to learn that, even as she was a vocal fan of groups like System of a Down, NOFX, and Nirvana, “Lavigne’s name became shorthand for the perceived archetype of a money-hungry industry plant co-opting the aesthetics of punk rock to make an easy buck” (90)–a tale that’ll be familiar to any number of music fans today.

The absolute most impressive part of the book, though, is that it brings it all back to these artists’ essential Canadianness. The book’s epilogue mentions the lasting marks these artists have left on the music industry’s rising stars, and they point to some rising punks that could be featured one day in a sequel, namedropping The Dirty Nil and Pup in particular–not to mention bands they leave out, like Arm’s Length, Single Mothers, and Counterparts, for example. Canada might be still waiting to get its due, but a book like In Too Deep is the first step.

––

Zac Djamoos | @gr8whitebison

The Alternative is ad-free and 100% supported by our readers. If you’d like to help us produce more content and promote more great new music, please consider donating to our Patreon page, which also allows you to receive sweet perks like free albums and The Alternative merch. And if you want The Alternative delivered straight to your inbox every month, sign up for our free newsletter. Either way, thanks for reading!